SIMÓN: The Weight of Guilt in the Fight for Venezuela

Movies as Vehicles for Change, Diego Vicentini's Story, Filmmaking, Dostoevsky, and Universality that Transcends Nationality

Si deseas, puedes leer la versión en español aquí.1

Over 7.7 million souls have fled Venezuela, marking the largest exodus in Western Hemisphere history. Each number carries a story of struggle, resilience, and the profound human cost of an unparalleled crisis.

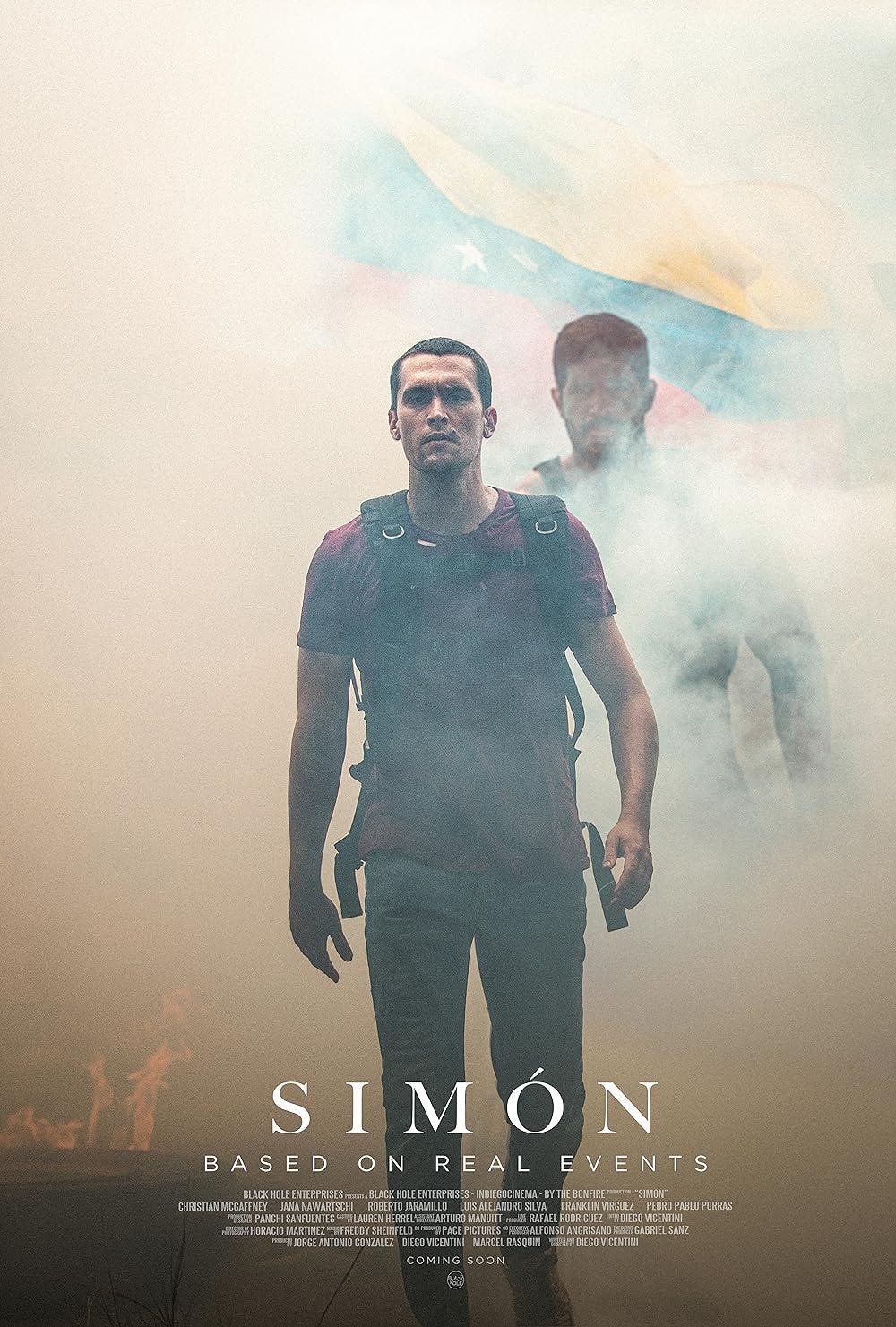

Recently, my family and I watched SIMÓN, a movie based on true events, depicting the inspiring story of a Venezuelan college student and freedom fighter who found himself at the forefront of challenging the tyranny of the Venezuelan government.

Simón, the protagonist, undergoes the brutal experience of capture and torture by the government. Following his release, he escapes Venezuela and lands in Miami, confronted with a challenging choice. He must decide whether to seek political asylum in the U.S., ensuring safety but forsaking any possibility of returning2, or to confront the oppressive regime in Venezuela, rejoining the movement and risking his life in unforgiving battles ahead. This decision weighs heavily on Simón, burdened with the guilt of abandoning his friends, the movement, and his homeland.

What will Simón do?

Table of Contents

SIMÓN: The Weight of Guilt in the Fight for Venezuela

Voice versus Exit

Venezuela's Turbulent Path: From Protests to Political Detachment in the 2010s

Is The Only Option To Leave Venezuela?

This isn’t a Dictatorship. It’s a Business.

Escape Velocity?

SIMÓN's Exploration of a Venezuelan Immigrant's Journey.

SIMÓN: A Cathartic Odyssey of Forgiveness and Healing

Young People Have All The Power (we just don’t know it).

The Story of Diego Vicentini

APT 17

ÆMBER

Still in 2019

COVIVID

Filming, Post-Production, and World Premiere

Make Something Authentic = Make Something Great

“Leave the country ASAP”

Timeline of Diego Vicentini

The Movie as a Vehicle for Change

Filmmaking: Non-Linear Storytelling, Color, Acting, and The Venezuelan Lingo

Non-Linear Storytelling

How the story of SIMÓN was crafted

Diego’s Storytelling

Color as a Narrative Tool

Acting

Music

The Venezuelan Lingo

My Favorite Shots & Scenes

The Essence of SIMÓN: Universality that Transcends Nationality

The Future

SIMÓN is a bat signal, brilliantly warming our hearts with the symbol of hope. This movie will hit you right where you don't want to be hit—in the heart—and it revisits a part of you that you wanted to forget: the Venezuelan within you. It reminds you of the pain associated with witnessing the country in its current state. The reason SIMÓN impacts you emotionally the way it does is that every Venezuelan immigrant, no matter who they are or where they are, sees themselves in Simón.

It’s a wake-up call to Venezuelans globally, myself included. Being one of the eight million Venezuelans forced to leave, it rekindled my love for my country, its people, and its culture. But it also reminded me of our profound losses, not just material possessions seized by corrupt dictators but, more significantly, our loss of hope.

We, as Venezuelans, lost hope. Once hope is lost, everything, absolutely everything is lost.

Losing hope for a better Venezuela is the feeling all Venezuelans have felt. It makes you wonder: Is the country something we lost and cannot get back?

Voice versus Exit

Well, these groups of students did not want to lose the country and risked everything—personal safety, aspirations, and more—in the pursuit of pride and a deep love for their country.

However, as the government's oppression escalated into violence, many suffered severe harm and even lost their lives. It is precisely during this tumultuous period that Simón is captured and subjected to torture.

You enter the movie theater as a Venezuelan who has reluctantly accepted the unfortunate state of the country, now living in a foreign land. But, when you leave, you depart as a Venezuelan driven to seek a solution.

I left the theater with hope and wondering: What’s the solution to the Venezuelan problem? The streets? International Community? The Opposition? None of those have worked. I don’t know what the solution is. But we need to find a solution.

The most fundamental concept in political science is known as voice versus exit. Let’s say a country or a company is in decline. What are your options? You can voice your concerns, trying to change things from the inside, or you can take the exit route. Voice is changing the system from within, whereas exist is leaving to create a new system, or join an already existing one.

In the context of a country, voice is voting, while exit is emigration. However, in a dictatorship like Venezuela, where fair elections are nonexistent, changing the system through voting is not an option. You might attempt to go to the streets, only to witness yourself and your friends being tortured, imprisoned, and killed. Meanwhile, just a few blocks away, people are dining and drinking Grand Old Parr as if nothing is happening. All the while, students are sacrificing their lives in a David vs. Goliath battle to rescue their country.

Does the Venezuelan problem have a solution? It's incredibly sad, and yet, for now, people seem indifferent.

Let me clarify, it's not that people don't care enough. These students gave a fuck. Heck, they were willing to give own their lives!!!!

But what happened? Well, people became demoralized. This didn’t happen in a single event. It happened slowly, after every protest, it was brutal with many injustices and lives lost. This killed people’s hopes for the country. Fear governs Venezuela. This is within reason after the endless agonies that Venezuelans suffered while those in government continued to be in power and terrorize whoever stood up against them.

Venezuela's Turbulent Path: From Protests to Political Detachment in the 2010s

The 2010s had many turning points. This was when we all thought this damned government would come to an end. The country was coming to the ground after years of mismanagement and corruption by the presidency of Hugo Chávez. An uncontrollable inflation, severe shortages of food and medical supplies, and the ironic failure of infrastructure in electricity and even gasoline. These served as tipping points that disturbed the nation and motivated multiple protests throughout the decade, notably in 2014 and reaching a climax in 2017.

While the opposition leaders encouraged the youth and filled them with the bravery they didn’t have, young people from all over the country took it upon themselves to go out to the streets to protest against the regime and call for change. But it was a slaughterhouse. Over one hundred sixty people were killed by the military during the protests, while hundreds or even thousands more were harmed, detained, tortured, and classified as “domestic terrorists.”

This generation of young Venezuelans gave up everything—lives cut short, careers left unfinished, and dreams extinguished.

SIMÓN is a tribute to the relentless victims who sacrificed their lives and hearts for their country. It also highlights the Catch-22 faced by all Venezuelans who, while carrying the trauma, find no relief whether they remain in the country or choose to emigrate.

These events shaped the course of Venezuela's future. Recognizing that the government was unlikely to change anytime soon, Venezuelans faced a binary choice: leave or stay. Those who chose to depart did so decisively, seeking new horizons. On the other hand, those who opted to remain embraced a mindset of political detachment, concentrating solely on navigating the complexities amidst the challenging circumstances.

That's precisely the approach adopted in today's Venezuela. The youth are largely apolitical3 and indifferent, and I can't blame them. If you haven't left or don't have imminent plans to do so, the primary focus becomes the struggle to make ends meet. Consequently, many are venturing into entrepreneurship, scraping together a living through minor retail trade and commerce, and figuring things out as best they can amid the uncertainty.

The young people of Venezuela want to live their lives. They witnessed the previous generation’s struggle, which seemingly yielded little change, as they remained trapped in the same dire situation. Today, the youth is determined not to replicate those past mistakes.

Adding to their skepticism is the fact that they have experienced numerous deceptions, particularly from the opposition. The constant exposure to falsehoods has cultivated a deep-seated mistrust, fueling their inclination to steer clear of political entanglements and focus on trying to have a better life.

Navigating this dilemma is like handing John Stuart Mill and Immanuel Kant a Rubik's Cube and asking them to solve it using ethical principles. It's not just about finding balance; it's about balancing individual rights and societal responsibilities – a philosophical puzzle that might make even these intellectual heavyweights reconsider their career choices.

The balance emerges as individuals seek their right to life, prosperity, and opportunities while grappling with the responsibilities tied to the collective – the society, country, and culture they belong to.

The weight is not just on their shoulders but on their very souls.

It’s undeniably complex, with both choices carrying rational and honorable aspects. But I cannot accept this balance. This isn’t what I want Venezuela to be. I want Venezuela to get back to the future, to be a country of opportunities and dreams, to be a country where talented and smart people from all over the world aspire to come, reminiscent of the aspirations of our grandparents when they arrived in Venezuela.

I don’t know where the next wave of change will come but it needs to come sooner rather than later.

Is The Only Option To Leave Venezuela?

For a young person living in Venezuela, your best option is to leave the country. Alternatively, if you choose to stay, you better make sure you know people in the military, politics, police, and anyone else who is corrupt.

Oh, and by the way, that's not enough. You not only have to know them but also hope they like you. Assuming both of those criteria are met, make sure you have a truckload of cash ready to hand over whenever they ask. And let's not forget about the criminals, kidnappers, and thieves—they're not much different from the military; they’re the same shit. There isn’t a line that separates them.

Let's say you decide not to pay them or do what they tell you. The consequence? You'll either end up dead, or the military/criminals will simply seize all your properties, or take your family away. Can they do that? The hell they can. They can do whatever they damn well please because there's no law, and they reign supreme in this country. You want to resist? Disagree? Express dissatisfaction? It's straightforward – they'll kill you and your family.4

So, yeah, I hope that’s clear—you cannot fucking stay without becoming a corrupt person because you'll be coerced into corruption up to the damn ground.

This is the reality Venezuelans are forced to endure.

This isn’t a Dictatorship. It’s a Business.

Venezuelans became aware of their vulnerability after witnessing hundreds of deaths at the hands of the institution presumed to be defenders of the people—the military. When you realize that the military and the criminals are essentially the same people, it's hard to wrap your head around it. However, it achieved its goal, which was to convey the government’s willingness to kill anyone who decided to rise up.

So, anyone, especially the youth, aspiring to fight for Venezuela will face only their own death or that of their families.

The government’s only objective is to stay in power, keep making money, divide the country, and oppress whoever they can, and so far, they’ve been successful.

In SIMÓN, there’s a scene that sends shivers down your spine. A colonel, tasked with quashing all protest leaders, confronts Simón to shatter him, strip away his pride, and plunge him deeper into corruption. The chilling words echo, “When will you understand that this isn’t a dictatorship? It’s a business.”5

This shatters your heart, and if that's not brutal enough, it throws those pieces into a shredder for total obliteration.

You experience the pure ideals of a youthful dreamer, Simón, collide spectacularly with the undisturbed cynicism of the colonel, whose power resides in the untouchable nature of his political protection and privilege. While Simón clings to principles, the colonel understands the students' deaths, freedom's loss, and justice's erosion are mere byproducts of a larger, intricate scheme of power and control.

Two opposing worlds - naive optimism and cynical realpolitik - crash together, leaving only wreckage where youthful hopes once stood. The colonel emerges unscathed, protected by the very corruption Simón has devoted himself to opposing.

"¿When will you understand this isn’t a dictatorship? It’s a business”.

- Colonel Lugo to Simón

Escape Velocity?

Venezuela became a country of haves and have-nots with crazy levels of economic inequality. Before, the have-nots had nothing and after, they had more of nothing, while those who had either got involved with the government and became “Enchufados6” or were forced to leave due to persecution. Those who remain, whether by choice or necessity, endure a daily struggle against government intimidation, economic struggle, and rampant delinquency, intensifying the divide.

What about the migrants you've likely heard about in the news?

It's a complex issue. The majority of Venezuelans immigrants are good and will contribute positively to the United States. However, like any country or large population, there are inevitably a few bad apples.

In Venezuela’s case, some individuals are referred to as the children of Chávez, as his socialist government created a generation of people who were provided with everything without having to work for it.

(Read more about the Venezuelan Migrant Crisis, here).

The concept of voice only works if “everyone” believes.

In rocket science, escape velocity is the minimum speed required for an object to break free from the gravitational pull of another, such as a planet like Earth. This principle holds true for social movements.

Can we generate enough "escape velocity" to break free from the clutches of a tyrannical dictatorship by accumulating widespread belief and participation in the movement? Despite numerous attempts, the Venezuelan freedom movement has yet to achieve the necessary escape velocity. With each setback, the challenge intensifies, making it even harder to gather the momentum needed to try again.

Learned helplessness is a real adversary, precisely what governments aim for you to succumb to. But fuck this. At the very least, becoming aware becomes our most potent tool in this struggle.

Often, the logical choice is to opt for exit, but there are times when abandoning everything isn’t feasible or you simply don’t want to, compelling you to fully embrace the path of voice. Personally, I align with the power of voice. Real change can manifest when we unite, wholeheartedly believing in a new future and a collective vision. However, life's fragility sometimes dictates that exit is the only solution.

So, how do we end the dictatorship?

Dismantling the dictatorship begins by exposing the incentive structures that allow it to leech off society and perpetuate corruption.

We must reveal the patronage schemes buying loyalty across military ranks, the backdoor deals trading complicity and impunity among crooked public servants, and the state-run rackets channeling public resources to enrich regime loyalists—all underscored by brazen cycles of corruption.

The way forward is to simplify these convoluted pathways built to obscure and perpetuate extortion.

Piece by piece, the people’s reclaimed power and prosperity will flow from dismantling and restructuring these crooked incentives.7

Ultimately, the keys to unlocking this systemic graft are transparency and unified citizen action. Venezuelans need to unite around a shared goal, whether it's reclaiming our nation or establishing a new one from the ground up.

SIMÓN's Exploration of a Venezuelan Immigrant's Journey.

What about adapting to the country you’re in right now?

That might be the path most people choose, not out of preference but due to a lack of alternatives, especially with no common goal in mind. I left Venezuela nearly eight years ago. Now, I barely have any family there, and even if there were a shift, such as a change in government with a reconstruction plan, the socio-cultural damage is extensive.

The essential social overhaul is critical for genuine change, which not only plays a role in shaping the required political and economic dimensions but also nurtures the sustainability and resilience of the country's long-term evolution.

An observation often shared by those returning to Venezuela is that the country has undergone such drastic changes that upon arrival, the immediate impulse is to leave again.

What one longs for is the era, not the place. The place is no longer the same; people have left, and things are different. The memories of that vanished era, shaping your perception of what the place was like, are no longer tangible; they exist merely as fiction in your mind, much like a vivid dream that dissipates when you wake up.

So, you begin adapting to your new country, forming bonds, and creating new roots. Will I ever come back? I have no idea. It depends on where, when, and whether I can make a change. When my friends ask me if I'll ever come back, I sometimes joke that I'll come back as president.

SIMÓN eloquently captures the essence of a Venezuelan deciding to start a new life in a different country.

After Simón arrives in Miami, the narrative explores the challenges of adapting to a new country with a distinct culture. The film focuses on the Venezuelan struggle in the United States, depicting the complexities of securing employment, grappling with homesickness, yearning for one's homeland and people, the involuntary erosion of hope, and the pursuit of political asylum. Through Simón’s eyes, we explore the trauma and pain experienced on multiple levels by those harmed by the government.

The United States deserves acknowledgment for establishing multiple avenues, such as Asylum, Temporary Protected Status (TPS), and parole, to assist in addressing the Venezuelan crisis. This deserves immense respect.

Why is the U.S. taking these actions? The Venezuelan migrant crisis is similar to Ukraine’s. Yes, a country in a war. It’s arguably equally or worse than Ukraine’s refugee crisis without billions of dollars in aid.

Simón endeavors to adapt and make a new life in a foreign land, but the journey is anything but easy.

The film becomes the first collective experience for Venezuelan immigrants of the adversities of what it’s like to immigrate. It brings together memories, struggles, uncertainty, and pain. It prompts a reflective internal dialogue that goes, “Damn, immigrating is tough, but I'm pulling it off.”

SIMÓN: A Cathartic Odyssey of Forgiveness and Healing

SIMÓN is powerful because it doesn’t tell you what to believe or what to think. It leaves it up to the viewer to draw their own conclusions. So, you leave the theater with a lingering sense of confusion, asking yourself, “Wait, is this movie about hope, or accepting to give up?”

You can leave the movie thinking that hope is lost, the country is fucked, and any effort is futile.

However, I refuse to see that as the message of the movie. It's not what the writer and director aimed to convey, even though it's easy to leap to the conclusion that these individuals tried and everything is lost.

The movie has a more subtle message, which is to become a catalyst for many Venezuelans to be more creative and find a solution. We only lose when we stop fighting.

If that message wasn’t subtle enough, there's an even more nuanced theme—that of healing.

Healing? Yes, healing. Venezuelans are wounded. Some physically, such as those tortured or killed by the government. Others are wounded emotionally, mentally, and economically. But collectively, we are all hurt.

SIMÓN is the start of a huge healing process all Venezuelans need to go through.

The film becomes an opportunity to heal the deep wounds we all carry and start finding yourself after those mixed feelings you’ve been carrying since you left Venezuela.

If you are going to take anything away from SIMÓN, take this away: the importance of learning how to grow, forgive, and keep moving forward.

SIMÓN guides you to give yourself forgiveness and empathize with the pain of your country. Even if pondering Venezuela is something we'd rather avoid, the film skillfully allows you to navigate those tough, almost unspoken emotions. Its brilliance lies in managing to draw out those challenging sentiments while simultaneously offering a subtle yet distinct sense of relief.

But it doesn’t end there. It continues because once we forgive ourselves, we need to forgive each other.

To understand all, is to forgive all.

- Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace.

In the film, Simón gets betrayed horribly. He does not comprehend how and why his friend would ever do what he did. However, once Simón understood the situation his friend was in, and how that led to the betrayal. Forgiveness became possible. To fully forgive, we need to fully understand.

What affects Simón the most is guilt.

He grapples with overwhelming guilt for leaving Venezuela, abandoning both his friends and the freedom movement, and something else I can’t tell you because it would be too much of a spoiler.

Many Venezuelans who left struggle with a sense of guilt, torn between the desire to be present and contribute to the freedom movement while also seeking a better life elsewhere. The helplessness was real, as they attempted to support their homeland from different countries during the years of protests, only to feel ineffective and, at times, foolish. After the protests' failure, there was a subsequent process of disconnecting and distancing yourself entirely from the country.

The film offers empathy and perspective on how individuals respond to the dilemmas arising from their personal criteria. It explains why some who left chose to disconnect and sheds light on the sentiments of those who stayed. This narrative enhances understanding and creates a path for forgiveness.

This also accomplishes another crucial objective—initiating a process of reconciliation between those who stayed and those who left. We must all forgive each other to be able to move forward and find a solution.

Before SIMÓN, it wasn’t clear to me. But now it’s clearer than ever that the reconstruction of our country does not start when the government changes; it starts today, and it begins with forgiveness. Forgiveness, not only for ourselves but for each other. United because we divided we fall guided by an unbreakable optimism to rebuild the country of our dreams. Learning from the mistakes of the countries where we all live, we envision to make Venezuela the greatest country on Earth.

Courage is not simply one of the virtues, but the form of every virtue at the testing point.

―C.S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters

SIMÓN is also a film about accepting one's limitations and serves as a historical exploration of the generation of courageous young individuals who were continually let down by both the government and the opposition. It grapples with the weight and responsibility of shouldering the task of saving a country.

The choice of the name SIMÓN for the movie is significant, especially for Venezuelans or those from South America. It immediately evokes thoughts of none other than Simón Bolívar. These young people, in their anonymity, embody the spirit of The Liberator, and anyone can see themselves in him. Bolívar is the ultimate symbol of liberty.

These young protestors left a tangible legacy in history and became unacknowledged heroes.

And if we talk about history, this movie itself became part of Venezuelan history. In fact, SIMÓN is history.

After I watched the movie, I texted a Venezuelan friend from college to ask him about the movie. He told me that SIMÓN affected him deeply for several days. Additionally, he mentioned his intention to show the movie to his kids once they come into the picture. I couldn’t agree more, and, in addition to SIMÓN, I plan to introduce my kids to films like Meet the Robinsons, 3 Idiots, and Accepted.

SIMÓN will become a tool to explain what is happening in Venezuela. I’d rather show you than tell you, and I’m sure I’ll show this movie to anyone who wants to understand what happens (and hopefully soon, happened in the past tense) in Venezuela.

SIMÓN, for me, will serve not just as a tool but as a potent warning. It stands as a cautionary tale for those who idealize leftist and socialist ideas. Venezuela is an example of when a country, whether due to bad luck or ignorance, falls into the hands of a socialist tyranny. While SIMÓN may appear to be a historical account, it's a living narrative of Venezuela today, echoing across Latin America and reverberating globally.

Watching SIMÓN is an urgent warning against an ideology that poses a threat to democracy worldwide. It's a call to action, compelling each of us not to passively observe but to actively assume our responsibility in shaping the future. The film urges vigilance against the erosion of democratic values in every corner of the world.

This movie will evoke heavy tears and stir deep emotion. You'll find yourself contemplating that what you witnessed feels like a relic from the past, something that unfolded decades or even centuries ago. Then, the realization hits — the movie hasn't concluded; the same harrowing events persist in Venezuela. It's precisely as the movie concludes that you're left with a profound feeling, whispering to yourself, “The movie is remarkable, but simultaneously, I wish it were not real. I wish it didn't exist, or at the very least, were merely fiction.”

Young People Have All The Power (we just don’t know it).

When you grow up, you tend to get told that the world is the way it is and your life is just to live your life inside the world. Try not to bash into the walls too much, try to have a nice family life, have fun, save a little money. But that's a very limited life.

Life can be much broader once you discover one simple fact, and that is everything around you that you call life was made up by people that were no smarter than you. You can change it. You can influence it.

That's maybe the most important thing, is to shake off this erroneous notion that life is there, and you're just gonna live in it. Versus embrace it, change it, improve it, make your mark upon it.

I think that's very important, and once you learn it, you'll want to change life and make it better because it's kind of messed up in a lot of ways. Once you learn that, you'll never be the same again.

SIMÓN reminded me of the power young people have to change things. In general, older people will try to tell you, you can’t do much and the world is the way it is, and that you have to accept it. But this reflects their own resignation, the limitations they've chosen for themselves.

But young people have the power, all the power, which some in power often try to suppress or distract you from realizing.

This isn't just a theme about Venezuela. It's a broader message about the power young people have to effect change, be it in your country, your state, your city, or even in your own university. Oppression exists everywhere, and young people, with sufficient belief in themselves, can and will change things.

First, you need to believe. It may feel like a leap of faith, but you must have belief because without belief nothing else matters. Belief will guide you, give you focus, and naturally help you start finding solutions.

Secondly, you need to trust yourself that the solutions you come up with will work, and if they fail, either keep trying or try something new, but keep trying. Failure is not a dead end but a lesson, indicating proximity to the solution. Trust in your ability to adapt and persevere.

Lastly, once you’re making progress, they will come after you personally either directly or indirectly so be sure to have a support group and be ready to give the fight back. Despite doing what's best, resistance can come, particularly from bureaucrats and those resistant to change. However, truth and authenticity will always win, even if not immediately, but certainly in the long term.

When something is important enough, you do it even if the odds are not in your favor.

—Elon Musk

These days people are too concerned with certainty and predicting how successful they will be when attempting something new. However, this facade of certain and obsession with the likelihood of outcomes misses the point. Who cares about the probability when it’s what you care about?

Ask yourself: What do you care about? I mean, what do you give a shit about?

Whatever that is, go ahead and do it with full conviction.

Coincidentally, this is the story of SIMÓN. The director, Diego Vicentini, started writing the movie when he was only twenty-five years old.

From a Hollywood perspective, this was a risky topic due to its specificity (focused on Venezuela), and probably wouldn’t do very well.

But fuck the “probablys,” SIMÓN is what Diego cared about. It’s the story he wanted to tell so he poured his blood, sweat, and tears into this film.

“Surprisingly,” SIMÓN became one of the most successful movies in Venezuela over the last decade. It secured a nomination at the 38th Goya Awards and even had the potential for an Academy Awards nomination. However, due to questionable voting rules and/or government intervention, the movie may have missed out on the Oscars.

I find Diego’s story incredibly inspiring so let me tell you more about it.

The Story of Diego Vicentini

Who is Diego Vicentini? An incredibly inspiring and promising filmmaker to watch out for in the future. More than a filmmaker, he’s a philosopher at heart, a characteristic that makes him stand out because he doesn’t just like making good movies or writing good stories, he wants to tell stories that make you think.

Diego was born in Caracas, Venezuela, and moved to Miami in 2009 when he was fifteen years old8. He completed high school and pursued studies in finance and philosophy at Boston College9. However, Diego's fascination with the combination of philosophy and film emerged early on during high school.

During this time, he stumbled upon a random DVD titled Match Point by Woody Allen. As he started watching, he realized it was a reinterpretation of Fyodor Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment, the work of Diego's favorite author.

This is when Diego realized film can be philosophy while incorporating elements like music, psychology, color, aesthetics, symbolism, metaphors, and more. For Diego, the seventh art is the most comprehensive of all artistic forms. Since that moment, he never turned away from the fusion of cinema and profound ideas.

Following his pursuit of finance and philosophy in college, Diego's trajectory took a turn during the summer of his freshman year. He participated in a one-month filmmaking program at the New York Film Academy, learning about writing, editing, and directing. During the program, Diego directed, wrote, and edited On My Way. Consequently, he ends up getting a Master’s degree from the same institution years later.

While studying philosophy, Diego developed an appreciation for the art of film, inspired by works such as Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan and Edgar Wright’s Scott Pilgrim vs. the World.

Throughout college, he maintained a double major in finance and philosophy, while also taking film classes. However, by his third year, Diego realized that finance did not resonate with him; it simply didn’t fulfill him. Diego wanted to do the thing even if he wasn’t paid for it.

So, after he finished college, he said, “Alright, cool. Let’s go study filmmaking.”

Before starting graduate school, he interned with a media company in Miami. Despite never having any social media presence, the company urged Diego to download Instagram to understand the format. But he didn’t want to start posting pictures of himself, he thought it was weird. Instead, he started @indiegocinema, a page for experimentation, creating video mini-projects to gain practical experience, improve, and receive quick feedback. This allowed for a quicker feedback loop compared to spending years on a movie before hearing reactions.

This Instagram page marked the beginning of the enigmatic "indiegocinema," which eventually became Diego's identity across social media and his media company's name. Through these videos, often blending deep philosophy with a humorous conclusion, Diego not only honed his skills but also discovered a profound realization about happiness and the purpose of his life—to live a life of creation.

In 2016, Diego graduated from college and had the balls10 to follow his filmmaking interests. He didn’t do it on the side, told himself he would come back to it, or whatever other bullshit people delude themselves with. Diego studied finance and could have gotten a job at a consulting firm or investment banking or whatever other job finance people do. He decided to give all of that up to follow his filmmaking interest.

“What a risk he took,” you might say! But the greatest risk of all is doing what you don’t want. This is what Diego wanted so this made the most sense, and I’m glad he followed his obsessions. Otherwise, SIMÓN would have never come to life.

After he finished university, he couldn’t do anything else than start his Master’s in Filmmaking in Los Angeles at the New York Film Academy, which he finished in September of 2018.

To graduate, Diego had to take on a difficult challenge—creating a short film as part of his graduate thesis11. His professor warned the students about the arduous nature of the thesis, advising them to choose a story or topic they intensely cared about. The rationale was clear: only with genuine commitment could they navigate the uncertainties, the moments of feeling lost and confused, the exhaustion, and the overwhelming desire to give up that go with every stage of the process, from writing and filming to editing, post-production, and distribution.

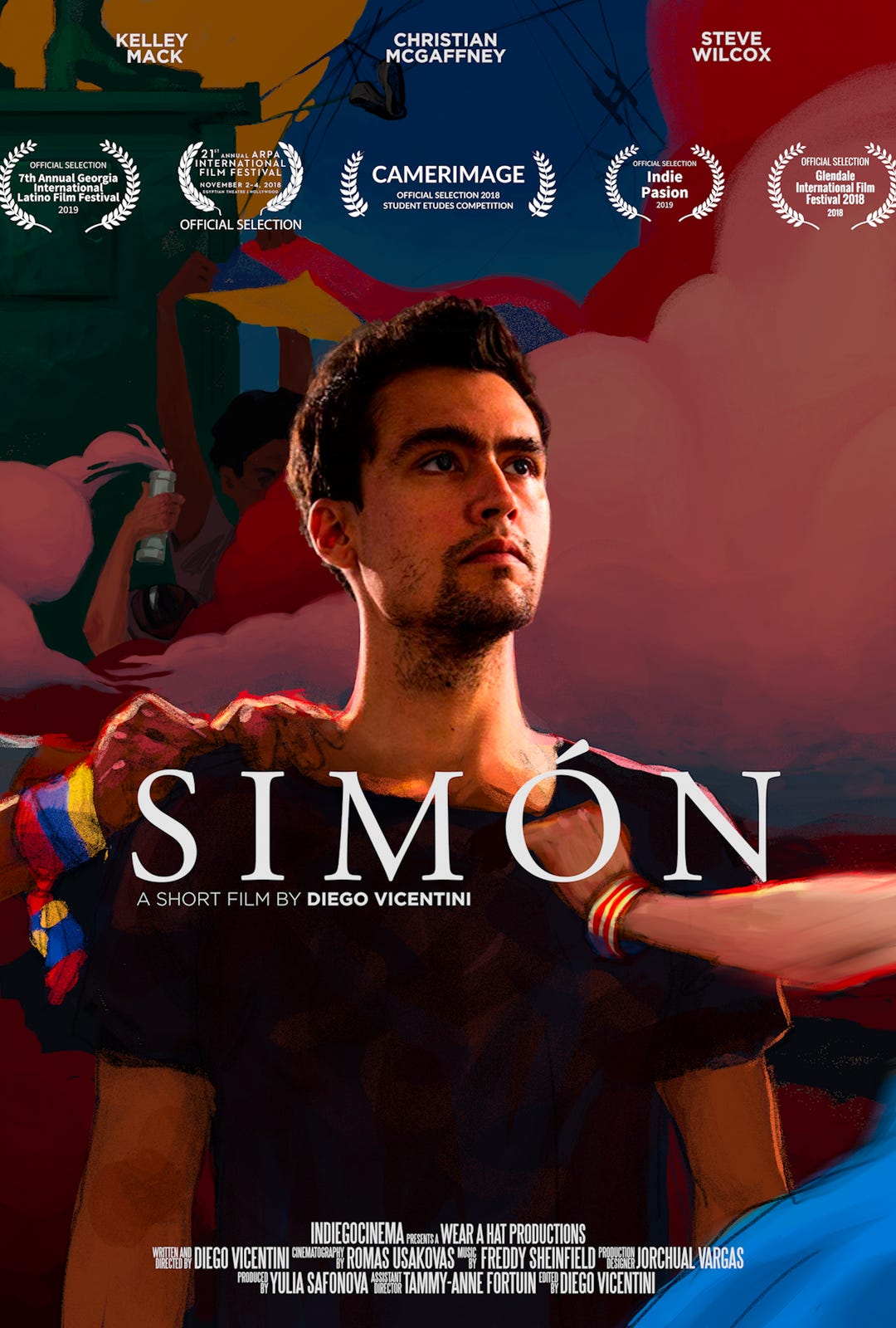

Diego chose to tell a story about a Venezuelan freedom fighter seeking asylum in the United States. Sounds familiar? Well, that’s because the movie SIMÓN12 movie started as a 26-minute short film.

To everyone's surprise, including Diego's, the short film received an unexpectedly high level of attention. Diego found himself on an independent worldwide tour, screening his short film in various countries. The trailer went viral, leading him to present Simón in around 8 countries, including Mexico, Panama, multiple cities in the US, London, and Madrid, where theaters were consistently sold out.

This overwhelming response became the driving force behind Diego's decision to create the feature-length version of Simón13.

And Diego went for it!

In 2019, he took the initiative and started a GoFundMe campaign. Alongside Marcel Rasquin, a well-known and respected Venezuelan filmmaker whom he had met at a volleyball game in Los Angeles, they successfully raised $35,756. Marcel, taking on the role of a producer, was drawn to Diego's vision.

After Diego circled the globe showcasing the short film, he reached out to Marcel for feedback on his idea. Marcel, having been in a similar situation years ago when he made Hermano, a film about two brothers aspiring to become soccer professionals in a baseball-centric country, recognized the potential. Just as Marcel had received support when he approached a producer, he felt compelled to do the same for Diego.

This is just the beginning—it's about to get even better.

After Diego shared a post about the film on social media, Jorge Antonio Gonzalez and Gabriel Sanz, two Venezuelan film producers from a company called Black Hole Enterprises, came forward to invest in and contribute to the project.14

Seeking financing is often the most challenging aspect filmmakers face, leading many projects to stall due to the high costs involved. But SIMÓN had a low budget. When that’s the case, you have to be resourceful. Being in Miami, where Diego's family had resided for many years, he knew that the Venezuelan community would offer substantial support. For instance, they needed a nightclub, and the first one they approached was owned by a Venezuelan who provided it for free. Similarly, a restaurant was needed for two days and it was offered without charge. Some locations were secured with the support of the Venezuelan community, who, upon learning about the film's theme, eagerly wanted to contribute. This immensely helped in reducing costs.15

Being resourceful is the most crucial aspect of being a filmmaker. Through Diego’s story, we can see the importance of the need to do things yourself, learn whatever is necessary, and be resourceful. It doesn't mean doing everything on your own but rather being unafraid to tackle any task and learn from others who may be more skilled. Diego's proficiency extends beyond his filmmaking and directing role—he designed the final movie poster himself, wrote the script, edited the movie, helped with distribution, and more.

Diego’s resourcefulness is what makes me certain he will be massively successful in the filmmaking industry. He isn’t afraid and is humble enough to learn anything he needs to get stuff done.

But that wasn’t everything Diego did in 2019. There’s more.

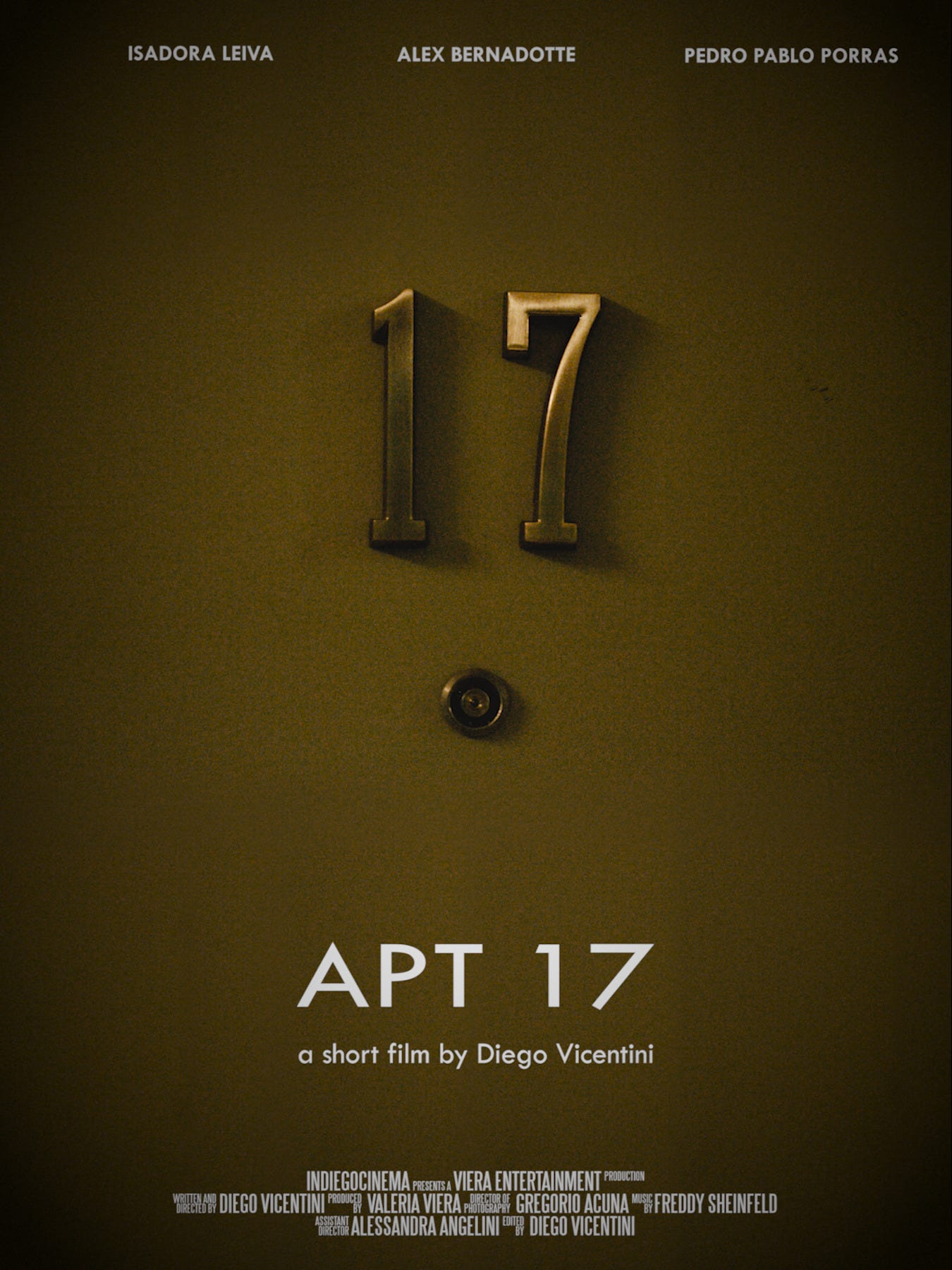

APT 17

In 2019, he made two short films16, both incredibly great. The first one is called APT 17, and it’s crazy good.

This is a film that prompts introspection, placing viewers in the shoes of the characters. From the moment the film begins, you automatically start asking yourself, “Would I do that?” or “Would I have done this?”

APT 17 starts with a drunk girl who gets forced into a guy’s apartment. However, appearances can be deceiving, and the storyline holds surprises for everyone involved.

A thrilling, humorous, and thought-provoking piece, it serves as a captivating thought exercise. Despite accumulating over 300,000 views on YouTube to date, APT 17 deserves at least 2 million views.

ÆMBER

Diego kept the ball (or camera) rolling and made ÆMBER, one of my all-time favorite short films. This piece is nothing short of a masterpiece, blending exquisite dialogue, captivating lighting, suspenseful storytelling, compelling acting, and profound philosophy.

The short film feels intimate, warm, and personal. When combined when its cinematic excellence and impeccably chosen fonts, the result is nothing short of an extraordinary cinematic experience.

You know when little kids watch a movie they love and watch it repeatedly; well, that's me with ÆMBER. I've watched this film at least twenty times. Each viewing is a joy, thanks to the color palette, emotional resonance, and overall cinematic experience providing endless satisfaction. The music, coupled with the initial awkwardness, creates a unique and pleasing ambiance. It's undoubtedly one of the most underrated of Diego’s works.

A particularly memorable moment in ÆMBER occurs when the girl in the film asks about Venezuela. It resonated deeply with me, echoing my own responses to the complexities of the situation. It wasn't just a mirror; it felt like a transcript of my usual words, delivered word for word.

Diego: I left 10 years ago, and I haven't been back. Things have only gotten worse there. I mean, people are dying on the streets. There's no food, there's no electricity, there's no gas, there's no medicine in the hospitals, and it's a mess. I always worry because I left, but now it feels like the home country that I feel I belong to doesn't exist anymore, and I don't know if we're ever gonna get it back.

Keana: (Awkwardly looks at him and looks away, unsure of how to respond. Diego quickly jumps in and switches the topic of discussion.)

Watching ÆMBER is when I realized that Diego is what I call a future self, someone who is ahead in their creative journey, and I could see myself making similar projects.

The depiction of shared interests in the film hits close to home, as I find myself working on a project that aims to create a new way how people meet.

Keana: Two people can have things in common, but it doesn't mean they're gonna have chemistry. I mean, you could say that you love nocturnal animals, too.

Diego: (interrupts and asks) Do you like nocturnal animals? Because I love…

Keana: I absolutely love nocturnal animals.

Both: (talk over each other about their fascination for nocturnal animals).

Diego: So we both like nocturnal animals.

Keana: Yeah, well, if we have one thing in common, that doesn't say much.

Diego: Inconsequential, really.

With Diego’s permission, I might even use this for my project’s promo video. It encapsulates this feeling and we aim it to do in a way that hasn’t been done before. Curious? Sign up for early access here.

In this specific scene, I love the audio design, particularly when both characters talk over each other, which adds a layer of authenticity and drama to the narrative.

The lighting in ÆMBER is truly exceptional—a remarkable accomplishment. My sincere appreciation goes to Horacio Martinez, the mastermind behind the lighting in this film. Horacio is the same person who also handled the lighting for SIMÓN, another masterpiece simply from a lighting perspective.

Every project is an apprentice to the next one, and you become more capable after their completion. You can see how Diego started putting the pieces together of a bigger puzzle without trying or even knowing. This happened by working with Horacio Martinez, who would end up greatly contributing to SIMÓN, and by making the short film Simón where Diego met Christian McGaffney, the main actor for the feature film.

Still in 2019

In the same year, he also made funny videos with Christian McGaffney and his wife, María Gabriela de Faría, both Venezuelan actors in the US. The videos are hilarious and well-made, and of course, they engage you in philosophical discussion.

Check out Vegan Beef and check out Raticas Ecológicas.

Moreover, in 2019, he started writing SIMÓN, a process that took more than eighteen scripts.

COVIVID

Then 2020 happened!17 We all know what happened: COVID! Great. It was a greater time for writing and finishing SIMÓN’s script. This is the time when Diego also made another short film called COVIVID.

If you weren’t sure of Diego’s talent, this is another validation.

COVIVID is a comedy horror that tells the story of a 20-something son eagerly awaiting his family for quarantine in their home in Miami. However, due to canceled flights, he finds himself alone, wrestling with the challenge of boredom, realizing that “the only thing scarier than the virus is boredom.”

The film is incredibly engaging, laced with suspense that keeps you glued to the screen.

I highly recommend watching COVIVID, and subsequently, viewing the behind-the-scenes video where Diego shares insights into the making of the film. It's fascinating to see how Diego involved his family, including his mom, dad, sister, and her boyfriend, in the filmmaking process.

My favorite part is when Diego ingeniously creates sounds and convinces his parents to participate in an awkward shot in the bathroom, I won’t tell you more about that.

And, the music!!!

The music in COVIVID, crafted by Freddy Sheinfeld, adds another layer of brilliance. Freddy, who later goes on to create the soundtrack for SIMÓN, is renowned for his work on popular shows like Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and the Yu-Gi-Oh! series.

Filming, Post-Production, and World Premiere

But Diego can do more than short films. In late 2020 and early 2021, he directed a music video for Holy War, a rock band. The resulting video is visceral, intense, and, of course, highly engaging.

Around mid-2021, Diego finished the filming of his first feature film, SIMÓN, within approximately 30 days and across 23 different locations. Each day brought a new setting, ranging from the beach to apartments and clubs.18

Between 2021 and 2022, Diego immersed himself in the post-production and editing process of SIMÓN.

Finally, in April 2023, the film came to fruition, receiving numerous awards in multiple film festivals.

These are Diego’s words when SIMÓN Premiered:

My First World Premiere.

It has now been a couple of days since the world premiere of my first movie @simonthefilm and I still find it difficult to describe, but I’ll try.

Most of the cast and crew were there. Reuniting with everyone two years later after shooting was special enough on its own. We really became a family in making this movie.

I sat farthest in the back of the theater. It was the most remarkable experience I have had as a filmmaker to sit there and hear and see the reactions the audience had to different parts of the movie. When they laughed. When they cried. When they cheered. When they flinched. When they cried again. I couldn’t believe it. SIMÓN was finally not ours, but theirs.

The movie ended and an applause started. And it continued. And it did not stop. For almost 2 minutes the audience applauded and for about roughly the same time I openly wept. It’s difficult to process the relationship between working on a project for 4 years and then this singular moment when it all becomes real.

(Swipe for that moment)

And then we went outside the theater and received an outpour of emotions. So many hugs and tears and beautiful words from everyone. A man who had been wrongfully imprisoned and tortured for years in Venezuela thanked us for making the movie and said we had captured how he felt. His trauma, his guilt, his conviction. At this point I think I dissociated and didn’t understand what reality was anymore.

I started writing this movie to honor and remember those we have lost in the fight for the freedom of our country while grappling with the guilt of not being there myself to fight alongside them. During postproduction, watching the movie over and over again, it transformed into a form of therapy - I began to see how many of the sentiments, thoughts, and emotions that I didn’t even know were in me were imbued into the film. It’s helped me bring to light, process, integrate and release a lot of what constitutes a complicated relationship with my home country, Venezuela.

Our first screening just about gave me a little hope that the movie might do for others what it did to me.

Thank you to everyone who helped me make it.

Phew, just incredible!

Make Something Authentic = Make Something Great

In every single one of Diego’s creations, two recurring principles always emerge.

First, caring about what you're doing is the only way to make something great.

Secondly, how do you make something great? By being authentic to your true self. If you like it, if you think it’s great, others will think the same.

Diego is an example of making things you genuinely care about, and if you do, other people will. Instead of trying to figure out what people want through market research or other nonsense. Do what you love!

To put it simply, being true to your authentic self and giving a fuck about what you’re doing is the only way to make something great.

He's not afraid to share his voice and tell the stories he genuinely cares about. No wonder his favorite artist is Jimi Hendrix, one of the most authentic artists of all time, not just as a guitarist but also in his way of being—how he dressed, talked, and captured his essence through his music.

In SIMÓN’s case, Diego felt he was moving farther away from Miami to Boston and then Los Angeles. The more time passed since he arrived from Venezuela in 2009, the closer he felt the urge to reconnect with his Venezuelan roots.

That’s why he decided to tell the story of Simón with the short film in grad school and why when he was only 25 years old, he started working on a full-length film, which became SIMÓN. He didn’t wait to get experience. He didn’t wait for inspiration to strike. He didn’t wait until the time was right. He didn’t lie to himself with all the lies people lie themselves with.

“Above all, don't lie to yourself. The man who lies to himself and listens to his own lie comes to a point that he cannot distinguish the truth within him, or around him, and so loses all respect for himself and for others. And having no respect he ceases to love.”

― Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov

“Leave the country ASAP”

Diego is not only authentic to his true self, he understands what it means to be courageous. As Mark Twain said, “Courage is resistance to fear, mastery of fear, not absence of fear.”

Choosing to make SIMÓN is a bold move, especially considering the potential consequences. Making a film showcasing the harsh reality of Venezuela is bound to displease the government. For Diego and everyone else involved, this meant potentially bidding farewell to their country. While he didn't have close family residing in Venezuela, returning could be ruled out.

When Diego approached actors for the movie, many declined due to the fear of government consequences or retaliation. Some contributors, including those who helped with the movie or donated, chose to remain anonymous, not wanting their names in the credits.

The ultimate test came when SIMÓN was nominated for the Venezuelan Film Festival. Diego along with the producer Jorge Antonio Gonzalez, had the guts to attend the festival in Venezuela, entering through the Colombian border while carrying the movie with them. Despite the surreal experience, the movie was showcased at the festival.

Diego’s decision to go to Venezuela wasn’t theoretically risky. There’s some bogus law called the "Ley del Odio" (Law of Hate), which could result in a 10 to 20-year prison sentence, Diego sought reassurance and was initially told not to worry. However, upon leaving, he received an urgent message to depart quickly. Fortunately, he was just ten minutes from the border, but those ten minutes were undoubtedly filled with adrenaline.

Despite the trouble and risks, SIMÓN achieved significant success, becoming the highest-grossing film in Venezuela since 2018, with over 100,000 people watching the movie.

Surprisingly, the government did not choose to censor or disallow SIMÓN; instead, it opted to ignore it, seemingly recognizing the Streisand Effect. Obtaining the permits was challenging due to seemingly irrelevant paperwork requests like asking for a Miami filming permit. But the team persisted and the movie eventually gained approval.

To date, SIMÓN was nominated for the Goya Awards and would have most likely been nominated to the Academy Awards (if it weren’t for some irregularities and/or government interference in the selection process).19

SIMÓN stands as a test for Diego and the entire team to keep fighting and get the movie to more people. It’s incredibly hard for an independent film to get distribution among theaters, especially if you don’t have a traditional distribution channel. In the usual filmmaking process, filmmakers secure a distributor and hope for the best. However, for SIMÓN, the team had to take a proactive approach, personally calling theaters and convincing them to show the movie.

Remarkably, the film achieved its success through grassroots efforts, relying on word of mouth rather than conventional advertising. The fact that it has reached theaters worldwide, even in suburbs like Chicago where I was able to watch it, is a superb achievement.

Diego Vicentini’s debut as a feature film director signals the beginning of an inspiring and impressive filmmaking career.

We know Diego is a prolific creator, and I’m excited about what he’ll doing next20.

I will be sure to support him on any future movies, and I would even love to work with him on any future projects.

Diego, if you’re reading this:

Avísame cuando estés filmando la próxima película, pana, porque me encantaría aprender y ayudar con lo que necesites: guion, filmación, producción, postproducción, conseguir actores, resolver cualquier vaina, todo. Mi amigo y yo hemos hecho varios cortometrajes; echale un ojo a algunos de los cortos que hemos realizado.

Y cuando quieras, te lanzas para Chicago y hacemos unos cortos calidad por estos lados.

As of today, Diego is already making plans for a second movie. You can support his new project by checking it out here.

If there is one thing to learn from Diego, learn the following:

Trust to create from your truest emotions and convictions.

Success may remain uncertain, but you will be certain people will connect with your work.

If people connect with it, chances are, it will be successful.

I undoubtedly connected with Diego’s work, otherwise I wouldn’t have written what you’re reading. For any future project, I aim to connect with people to the point where a random kid writes a mini book about my work.

As you move forward with your life, ask yourself: What do you feel? What emotions drive you? What stories do you want to share? What do you genuinely care about?

Timeline of Diego Vicentini

1994 — Born in Caracas, Venezuela

2009 — Moves to Miami, United States

2012-2016 — Enrolls in Boston College studying Finance and Philosophy

June 2013 — Participates in a summer program at the New York Film Academy

2016 — Graduates from Boston College

2016 — 2018 - Pursues a Master’s Degree in Filmmaking at the New York Film Academy

2018 — Creates the short film Simón

2019 — Makes ÆMBER, APT 17, and other videos

2019 — Initiates the scriptwriting process for SIMÓN

2020 — Makes COVIVID

2021 — Directs a music video for Holy Wars

2021 — Filming of SIMÓN

2021-2023 — Engages in the post-production of SIMÓN

April 2023 —Releases SIMÓN

November 2023 — Nominated for Goya Awards

2024 — Diego celebrates his 30th birthday

The Movie as a Vehicle for Change

You know what’s cool about movies? You can write history.

Sometimes, more than writing, you can make and inspire future history that hasn’t been written yet. SIMÓN is a catalyst for the ongoing fight for liberty in Venezuela, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the movie inspires the next wave of change.

The pen might be mightier than the sword, but when it comes to change, a heartfelt story with cinematic power can rewrite history and inspire revolutions.

Movies continue to be a powerful medium for raising awareness on a grand scale. There's a unique and cathartic essence to a film, a storytelling method that shows rather than tells, profoundly impacting the viewer.

Along with a friend, we realized filmmaking’s role in shaping perceptions and inspiring change in the world so we started making movies, and a few months ago, I wrote:

The impact and power of good storytelling are inspirational in their ability to illuminate the human spirit, initiate change, and connect us on a profound level.

It reminds us that, as storytellers and as listeners, we are all participants in the narrative of life, capable of inspiring, transforming, and leaving an unforgettable mark on the world through the stories we share.

Our goal [making movies] is to instigate ambition, encourage fearlessness, inspire people to discover their calling, and, most importantly, follow their curiosity.

My friend and I want to make the following movies:

Fear, Ambition, and Fully Living: Our goal is to instigate ambition, encourage fearlessness, inspire people to discover their calling, and, most importantly, follow their curiosity. We haven’t quite figured out the story yet. But the basic idea is many people are fearful of people, the future, and themselves. This affects how ambitious you are as you can always do more than you think. Plot twist: It’s not about ambition, it’s more about finding the medium where you can express yourself and become ambitious, and therefore, “ambitious.” It also explores learning how to care about something (finding meaning), trusting yourself and others, and living your life without hesitation.

Abundant Energy: Imagine a universe where energy is abundant, and physical and digital resources are free. In this world, work is optional, and the central theme revolves around the search for meaning. The film intricately weaves the story of a child who ingeniously extracts energy from everyday things, providing a captivating narrative that explores both the pursuit of meaning and the abundance of energy.

Beyond the Script: Aanya challenges Indian parental expectations, education norms, and societal pressures, creating a meta-film about her struggle to break free and pursue filmmaking. The narrative blends humor, emotional depth, and relatability, exploring the dichotomy of choices in engineering, arts, and entrepreneurship. A witty twist reveals that the movie viewers just watched is Aanya's own creation, strategically crafted to propel her toward filmmaking success. Beyond the Script promises a thought-provoking journey of self-discovery, family dynamics, and the pursuit of dreams in the face of societal expectations.

When I think about the things that have impacted me the most, movies always come in the top 5. It’s extremely multi-disciplinary as it allows you to combine any of your interests no matter what they are. Whatever you want to include, you write in the script, think about how to do it, and you do it.

I remember when Christopher Nolan decided to be a corn farmer after he needed a cornfield for Interstellar. He did not want to use computer-generated imagery (CGI) so he spent about $100K planting corn in Calgary, Canada. Many experts said the corn would fail to grow. Not only did Nolan get a good crop for the unforgettable drone scene, but also he made some money on it.

I cannot think of any other jobs that allow you to do things like that. Of course, you have to reach Christopher Nolan’s level first.

If we talk about Nolan and movies, I need to remind you.

When you watch SIMÓN, please please please watch it in a movie theater. This is for multiple reasons. First, you can support the filmmakers. Second, the sound, the size, and the ability to immerse yourself fully can only happen in a movie theater. Lastly, as Édgar Ramírez said, it’s about “experiencing the collective catharsis that comes with watching Simón in a movie theater.”

Filmmaking: Non-Linear Storytelling, Color, Acting, and The Venezuelan Lingo

SIMÓN is a tour de force of genres, a complete and captivating cinematic experience. The movie surprises you at every turn and it seamlessly incorporates together elements of suspense, action, adventure, comedy, romance, and thriller, creating a rollercoaster of emotions for the viewer. Based on true events, the narrative evolves through different, non-linear plots that add depth and complexity, keeping you engaged and glued to the screen.

Non-Linear Storytelling

SIMÓN tells the story of the torturous journey of a young Venezuelan, transitioning from an organized protester to a prisoner and eventually a U.S. asylum seeker. The film uses a non-linear storytelling technique, presenting the events out of chronological order. This deliberate choice allows the audience to piece together the narrative gradually, strategically revealing information.

The result? An intensifying watching experience that heightens the suspense, and mystery, and allows us to explore the psychological aspects of the characters.

This narrative style plays a crucial role in SIMÓN making the story dramatically intense. By defying the traditional chronological sequence, the climax of the movie becomes much more painful and feels more organic.

The nonlinear narrative of SIMÓN resembles an X-shaped story arc, with the two distinct strokes intersecting at a pivotal point:

Simón in Venezuela (Downward Stroke/Red):

Highest Point: Simón’s life in Venezuela is at its peak, representing the beginning of the storyline.

Inciting Incident: Simón’s capture is a significant turning point that shatters the initial stability.

Conflict and Descent: The narrative goes into the challenges and hardships Simón faces, illustrating his descent from the peak.

Simón in Miami (Upward Stroke/Blue):

Lowest Point: Simón’s life in Miami portrays him as broken and in a state of despair.

Rising Action: As the story progresses, Simón starts rebuilding his life, climbing from the lowest point.

Resolution: The narrative reaches a high point again, showcasing Simón’s journey toward redemption.

The intersection of these two strokes creates a unique storytelling structure, allowing viewers to piece together Simón’s complex journey, making the nonlinear narrative a key element in conveying the depth and complexity of the character's experiences. This structure also adds layers to the narrative, emphasizing the contrast between Simón’s life in Venezuela and his struggles in Miami.

When the arrows in the X-shaped story arc intersect, Simón’s highest and lowest points in Venezuela and Miami meet, and this creates a mesmerizing narrative that captivates viewers.

How the story of SIMÓN was crafted

SIMÓN concludes with an open ending, leaving the audience in a state of contemplation long after leaving the theater.

This deliberate choice aims to engage viewers in a prolonged reflection. It provokes thoughts that keep you up at night. Unlike movies with neatly tied-up resolutions, SIMÓN challenges its audience by withholding clear emotional closure.

Simón’s story is a composite based on the real experiences of many different people. Diego skillfully blended multiple perspectives into one central character. This dimensional approach creates a protagonist who profoundly embodies the struggles of both individuals and a nation grappling with turmoil.

Diego's approach is different—he isn't making feel-good flicks. Instead, he aspires to create films that remain within you, prompting internal reflection.

By not providing a straightforward emotional resolution, he pushes viewers to wrestle with complex feelings and encourages introspection. If you don’t know how to feel what you’re feeling, you have to think to try to figure it out.

Diego enters your mind using an emotional trojan horse, and once he’s inside he wants to engage with you at an intellectual level, prompting you to reflect and question your emotions: “Why am I feeling like this?” “Am I happy?” “Am I sad?” “What exactly am I feeling?”

The only way out is through introspection. This dual approach, blending emotional impact with intellectual stimulation, defines Diego's storytelling, urging the audience to explore the depths of their thoughts and feelings.

Perhaps, that’s why I wrote this essay in the first place, to figure out what I was feeling.

Diego’s Storytelling

Diego's process of storytelling often starts at the end, intertwining it with the beginning.

This approach serves as a bridge, guiding the narrative flow.

How does Diego figure out the beginning? He asks himself key questions such as, “What do I want to say? and “Why do I want to say it?”

This suggests the beginning, setting the tone and purpose. Ultimately, this leads to the inception of the story.

He knows the end and he knows the beginning. But what about the middle?

The second act is always the hardest to fill. This involves determining which characters fulfill specific functions to reach pivotal moments or conclusions. Diego navigates this process, considering the characters' roles in crafting the narrative's progression.

While the process may sound straightforward, crafting a truly exceptional story demands iteration, often starting anew multiple times. In SIMÓN’s case, this rigorous approach led Diego through 18 script iterations—an example of the dedication and persistence required to refine and elevate a narrative to excellence.

Color as a Narrative Tool

When the students in Venezuela are celebrating the birthday of a friend who lost his eyes due to government oppression (this actually happened, by the way), and then, after the birthday party, they are coordinating what future protests, every character is wearing the same color palette. However, there’s one figure who does not follow this color scheme. This figure ends up being the Judas Iscariot of the movie and betrays Simón, this character is depicted in the color red, symbolizing allegiance to Chavismo.

When we encounter the betraying character again in Miami, he’s no longer dressed in red and confesses why he took the actions he did.

Notably, Chucho, representing the antithesis of red, is portrayed in blue.

Simón maintains a neutral color scheme throughout, which reflects his complex character.

In SIMÓN, the film's meticulous color choices not only become apparent but also contribute to the storytelling at a subconscious level.

Color, lighting, and photography, among other elements, showcase Horacio Martinez's exceptional talent. The shots of Miami, offering serene sunsets while the protagonist navigates inner chaos, or the shivering colonel scenes, to shots showcasing Venezuela—all add layers to the visual narrative of the film.21

Acting

Let’s talk about acting!

Christian McGaffney delivered an outstanding performance as Simón, the protagonist, skillfully navigated heavy introspective moments. He internalized the battle of accepting the past and determining his future, portraying a character trapped in the never-ending present, grappling with trauma, guilt, and the quest for a solution.

Additionally, in Venezuela, a leader emerged, capable of sparking a movement. On the flip side, in Miami, he portrays another character as a subdued, depressed individual burdened with guilt. These dual portrayals added depth and contrast, showcasing the complexity of the characters' journeys, and Christian’s acting ability.

Franklin Virgüez, in the role of the intense and cynical colonel, delivered the performance of a lifetime. In a 4-minute and 50-second appearance, he skillfully conveyed his cynicism and menace, leaving a powerful impact. Every gesture carried a force, and his gaze was penetrating. His performance, inspired by the short film La Tumba, resumes the entire movie.22

Roberto Jaramillo portrayed Chucho, a character designed as a pressure relief valve, offering a comedic release. Like a valve, Chucho opens at a preset pressure, providing relief until levels normalize. In his first acting role, Roberto brought the typical charismatic Venezuelan charm, discovered through social media after responding to a casting call. Standing at an impressive 6'3", Chucho's character adds surprising depth to the story, showcasing Roberto's remarkable debut and leaving audiences captivated by the film's richness.

Chucho illustrates what the typical Venezuelan friendship is like, loving and unconditional.

Jana Nawartschi, portraying Melissa, and Luis Silva, playing Joaquín, both did an incredible job showcasing various facets of Simón's character. Their performances added depth and nuance to the portrayal of Simón's journey. Each actor brought their unique talents to the roles, enhancing the complexity and richness of the narrative. Additionally, José Ramón Barreto contributed a formidable antagonist force, delivering a wonderful performance that added another layer to the film's dynamics.

Music

The addition of Venezuelan artist Danny Ocean's Me Rehúso in the scene where it was used is one of the most vibrant and touching scenes. This is one of those times where the right music can enhance your emotional response, and Me Rehúso was pure perfection. The synergy between the song, the movie, and the seemingly palpable love in the air creates an unforgettable moment.

In many ways, the lyrics of Me Rehúso encapsulate what Simón was going through. Diego wrote this part of the script with Me Rehúso in mind even before he knew whether he could use it. Eventually, Diego meets Danny Ocean and helps coordinate with the record labels to use it in the movie.

When Simón and Melissa start dancing Me Rehúso as if it was Merengue tells you everything you need to know about American culture.

Along with Danny Ocean, Freddy Sheinfeld, another Venezuelan film composer also stole the show with an unbelievable soundtrack for the movie. See and listen to the soundtrack.

The Venezuelan Lingo

If you don’t speak Venezuelan Spanish, SIMÓN won’t be as fun, but if you’re Venezuelan, you will have a ball!

I’ll give you an example.

In Venezuelan: ¡Coño, vale, eso está arrecho!

In-theater caption: Wow, man, that's tough!

Literal translation: Fuck, that's really fucked up!

Or a more juicy example:

In Venezuelan: ¡Mira, mamaguebo. Deja la mariquera!

In-theater caption: Look, fool. Stop it.

Literal translation: Look, dicksucker. Stop your fuckery.

It’s hilarious and something you can’t translate into English.

It sounds way too strong and something you don’t really say (unless you mean it). Besides lacking the tone and body language, it lacks the colloquial warmth and camaraderie embedded in Venezuelan interactions.

These phrases reflect not just the linguistic richness but also the informal, friendly banter that characterizes Venezuelan communication. It’s a big part of the culture.

Another example:

In Venezuelan: Pajuo, ¿me estás jodiendo? Ya me estás arrechando.

In-theater caption: Dude, are you kidding me? You’re pissing me off.

Literal translation: You fucker, are you fucking with me? You’re fucking shitting me right now.

Even if you’re not fluent in Venezuelan or Spanish, you will start wondering, what does the word Guevón mean? And why do they say it so often?

I was wondering the same thing. How many times did they say Guevón?

I did my research and found someone named Josué Reveron who went to watch SIMÓN twice to simply count the number of Venezuelan expressions.

I have no way of confirming. But according to Josué, Guevón was said a staggering number of 64 TIMES!!!

If you’re curious, here’s the entire list of Venezuelan expressions according to Josué:

Guevón: 64

Marico: 28

Coño: 18

Cagao: 10

Vaina: 9

Coño e’ la madre: 7

Mamagüevo: 4

No joda: 4

Pajuo: 3

Jodido: 3

Güevonada: 2

Coño e’ tu madre: 1

Carajitos: 1

Cara de culo: 1

Mamamelo: 1

Chamo: (not counted but at least 20)Edited for clarity, see the original quote.23

Consider yourself proud if you pick up a word or two. Speaking Venezuelan is not just a skill; it's a luxury and a status symbol.

My Favorite Shots & Scenes

These are my favorite shots and scenes:

The Colonel scene: The monologue with the Colonel was incredibly terrifying, and when coupled with an excellent lighting and acting job, it becomes the most memorable moment of the movie. The lighting in this scene was exceptional. The light bounced at the perfect level and angle, complemented by precise color correction to bring out the shine in the eyes. The light source was positioned from top to bottom, enhancing the overall visual impact of the scene.

Zoom Meetings Scene: This was incredibly creative. In Simón’s Zoom meetings with his friends back in Venezuela, they didn't just show him as a person on the screen. Instead, when Simón spoke, they portrayed him as if he was physically present with them, sitting on a similar school seat in the same classroom. The innovative approach added a unique and engaging visual element to the scenes.

Dominoes Game Scene: This reminded me of the many weekends spent playing dominoes with my grandpa and his friends. However, this scene takes a sudden and brutal turn, deviating from the nostalgic atmosphere.

Orange Juice Scene: This was surprising because everyone, including the viewer, initially thought the prisoners were being showered with gasoline, anticipating a horrifying turn of events. However, it turned out to be orange juice, which seemed harmless at first until its consequences unfolded a few hours later. Diego’s incredible research shines through, and when he showed the movie in different countries in South America, many attendees shared that similar incidents had happened to them. The authenticity portrayed in the scene resonated as “too real,” according to their accounts.

The Breaking Scene: This scene, filmed 14 times, emerged as a climactic moment on set. As Diego and the crew witnessed the emotional climax of the film unfold authentically, they realized they were crafting something truly special. In this intimate setting, with only essential crew members present, the depth of the performance moved everyone to tears, marking a profound connection to the story. The unplanned emotional response, including the director and crew crying, signaled not just a scene but a genuine, impactful movie in the making. This experience affirmed the power and authenticity behind the creation of SIMÓN. This is when they knew they had a movie when the guy who wrote it started tearing up, and the impact on everyone else (more than 50 people) present during the 14th take was a clear sign of something extraordinary, something special.

The Final Hug: SIMÓN is defined by hugs. Each hug is an important pillar of the story that makes it stronger and stronger as it evolves. This shot was Horacio Martinez's favorite.

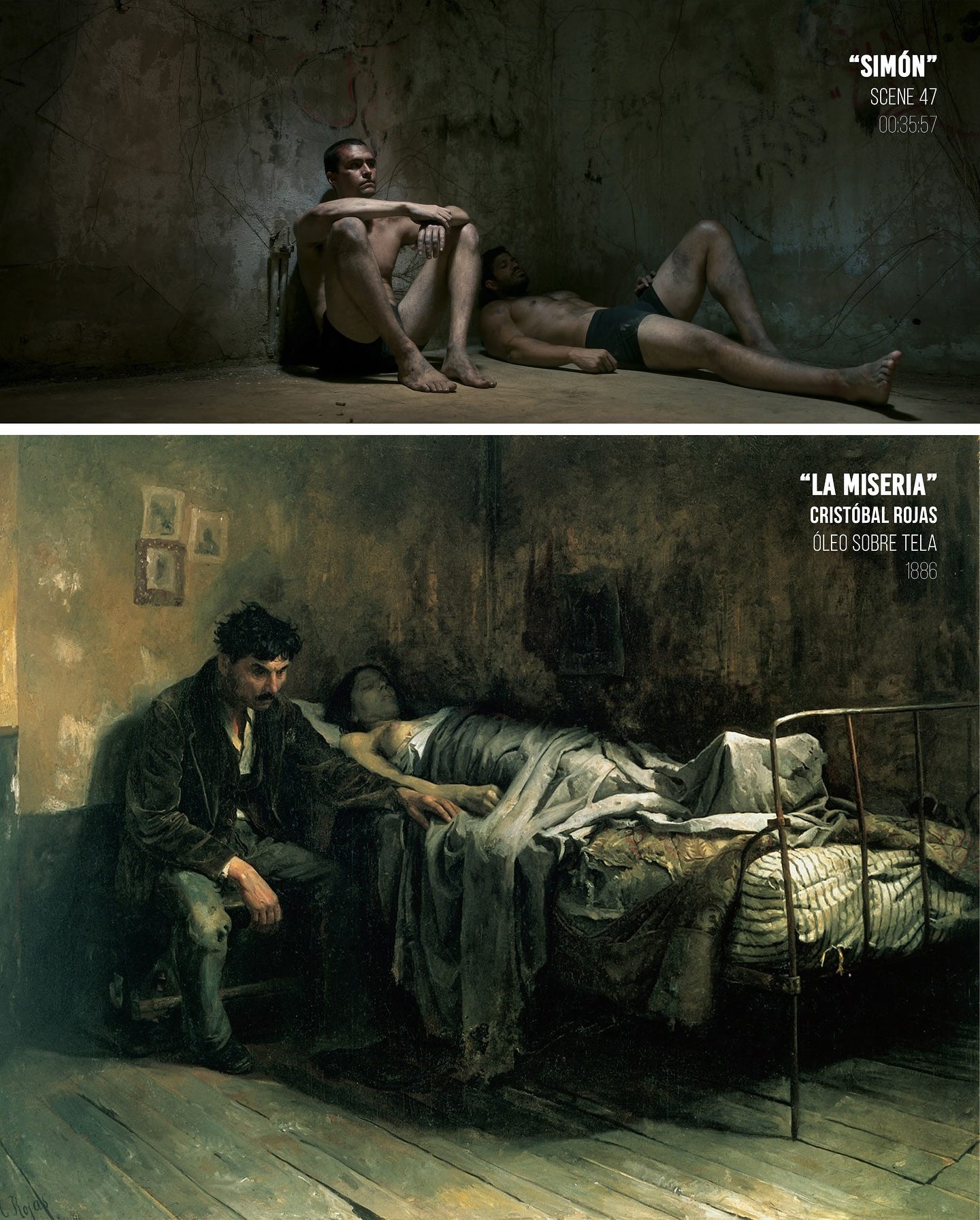

Paintings: A couple of key scenes in the movie were inspired by paintings by Venezuelan artist Cristóbal Rojas. The way these moments visually connect with Rojas’ work adds so much depth and emotion to the story.

“La Miseria” (1886)

Oil on canvas

This painting really nails the mood for that intense scene in the dungeon where Simón and Chucho are locked up. It captures the hopelessness of political prisoners in Venezuela—just like how Simón and Chucho are feeling. The whole vibe of the painting foreshadows what’s coming for them. It’s dark, it’s heavy, and it helps to set the tone for what they’re going through on a deeper level.

“La Muerte de Girardot en Bárbula” (1883)

Oil on panel

This one comes to life in the scene where Juanchi gets shot in the face by the National Guard (GNB) and falls back, still gripping the flag. It mirrors the same energy as Rojas’ painting, where the hero dies but refuses to let go of the flag. It’s such a powerful moment because it’s more than just a guy getting shot—it’s about the sacrifice and determination to stand up for something bigger. In a way, the fight for freedom continues, both in the past and the present.

The Essence of SIMÓN: Universality that Transcends Nationality

The story, in SIMÓN, is universal because the emotions it portrays are universal. You don’t need to be from Venezuela to understand the movie. Anyone who has experienced being a refugee, regardless of their country of origin, will resonate with the narrative. Whether it's someone from Ukraine, or someone forced to leave their homeland, the feelings depicted in the movie are relatable and will move you.

SIMÓN has a character for everyone.

For those not from Venezuela, some characters serve as guides, helping to learn and gather the necessary context about the country and its experiences.

For those from Venezuela, some characters represent and reflect the diverse array of emotions and sentiments that one might feel, creating a relatable connection with the narrative.

Additionally, the story itself is well-developed.

For example, there is a crazy plot twist no one expects. I did not expect and once we found out, it hit me intellectually because I did not see it coming, and of course, emotionally because I did not want to believe it.

While avoiding unnecessary graphic depictions of pain and suffering, SIMÓN effectively conveys the emotional weight of the narrative. Diego's philosophy is simple: if it’s not needed, it’s just extra and unnecessary.

The “love story” in the movie is subtle, leaving room for interpretation. The ambiguity surrounding Melissa's role as a potential girlfriend adds depth to the narrative. The film avoids clichéd scenes or stories that typically involve a kiss and a resolution.

Diego channels his inner Dostoevsky, portraying characters where finding joy becomes a form of punishment. Pleasure only serves to accentuate the profound suffering that his characters endure.24

Notably, SIMÓN refrains from focusing on politics. Instead, the spotlight is on the true victims of the Venezuelan humanitarian crisis: the people. Diego subtly highlights the futility and cruelty present on both sides of the Venezuelan political spectrum.

What is SIMÓN’s Message?

To make you think, reflect, forgive yourself, and keep fighting for Venezuela.

It’s certainly not to lose hope25. Yes, our country has been exhausted by false promises from all sides over and over again. Rebellion has left only deaths and the government has been there for almost three decades and does not seem to be ending anytime.

"To live without hope is to cease to live."

― Fyodor Dostoyevsky

But as banal as this sounds, we cannot lose hope, because the moment we do, Venezuela ceases to exist. It has certainly ceased to exist in a good portion of the eight million who have left, and that’s exactly what the government wants.

The future of Venezuela is uncertain. However, SIMÓN is a reminder for every Venezuelan about their origins, and hopefully, a reminder to keep your hope.